“It is idle to attribute the relief of pain to a substance given in a series of injections when the ritual of the treatment itself, as well as numerous other factors that have not been excluded, could have been responsible for the change” (Gold 1939, p. 6).

In his seminal history of blind assessment, Ted Kaptchuk traces the history of “intentional ignorance” in medical research from the 18th century skeptical evaluation of mesmerism, through the attachment of double-blinding to the mid 20th century randomized controlled trial as the embodiment of the hard science of clinical medicine (Kaptchuk 1998). Having focused attention on the late 19th century and early 20th century European concern with “suggestion” (and its likely impact on such early 20th century German researchers as Adolf Bingel and Paul Martini), Kaptchuk nevertheless suggests that such concerns regarding suggestion were slow to cross the Atlantic. He thus grounds the Anglo-American interwar incorporation of blind assessment into clinical research not in terms of “continental concern with suggestion,” but rather as “technical organizational problems” (ibid, p. 422).

And yet, Anglo-American studies of the treatment of angina pectoris – the debilitating chest pain considered by then to accompany coronary artery disease – would not only play the key role between the 1930s and 1950s in the formal advent of the “double-blind” study within American clinical pharmacology, but would be grounded from the 1930s onward in concerns over “suggestion” and the impacts of anxiety, context, and the apparently alleviating effect of the act of providing medication itself in the course of the experience and evaluation of anginal pain.

No one would be more central to the ascendance of the “double blind”1 as a key component of angina evaluation, and of rigorous clinical trial methodology more generally, than Cornell clinician and pharmacologist Harry Gold. And Gold saw the double blind as only one methodological component – albeit a crucial one – that elevated therapeutic evaluation beyond mere “clinical trials” to what he termed “clinical pharmacology” (or “human pharmacology”), approximating the rigor of the laboratory and capable of separating pharmaceutical wheat from chaff. Yet Gold, focused on the internal validity of the experiment, was not without his own blind spots concerning the larger therapeutic ecosystem in which such drugs were introduced and evaluated. This paper, with angina and Gold as its focus, situates the advent of the double blind amidst such clinical, academic, and industrial concerns during a crucial period in the history of the controlled clinical trial.

Angina Relief and Suggestion

From the 1920s through the 1940s, the scattered Anglo-American application of patient and/or researcher blinding extended to therapeutic domains as diverse as the common cold, psychiatric disease, and tuberculosis (Shapiro and Shapiro 1997; Kaptchuk 1998; Rasmussen 2005; idem 2008; Gabriel 2014). Yet by mid-century, the most sustained flow of such interventions related to angina pectoris. Angina, by this time, was largely considered to stem from coronary artery disease. Nevertheless, hearkening back to earlier notions, anginal pain was still considered by many as modified by the nervous system and other “constitutional” aspects of the patient (Aronowitz 1998). As New York clinician Harlow Brooks stated in 1935 at a New York Academy of Medicine symposium: “Physical factors are often much subordinated to emotional ones in this complex and the social obligations and psychic reactions of the individual sufferer are usually of equal if not greater import than anatomical ones” (Brooks 1935, p. 442). In turn, those evaluating the efficacy of treatments of anginal pain, even if those interventions were geared towards the coronary anatomy, would have to grapple with the overlay of such “psychic reactions.”

This would play out initially with respect to the apparently vasodilating xanthine drugs, though would extend to other pharmaceutical interventions as well. As far back as 1896, in Königsberg, Askanazy had alternated patients – in what would today be considered a “crossover” design – to periods of treatment and no treatment, concluding that “with the certainty of an experiment the attacks disappeared at once” (Askanazy 1896; as translated by Freedberg, Riseman, and Spiegl 1941, p. 495).2 By 1929, researchers at St. Luke’s Hospital in Chicago and Northwestern University Medical School administered xanthine preparations to eighty-six patients, with no comparison periods or patients, finding relief in seventy-two of them while acknowledging the difficulty of evaluating “a symptom complex so readily influenced by nervous factors” (Gilbert and Kerr 1929, p. 203). A year later, the American Medical Association’s Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry favorably reviewed the “therapeutic claims” for such agents, based on in vitro evidence of coronary artery vasodilation, animal studies of increased coronary blood flow, and such clinical data (Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry 1930).

Three years later, however, William Evans and Clifford Hoyle, at the London Hospital, noted with respect to anti-anginal drugs that “there has scarcely been a methodical attempt to compare the relative values of the many drugs that have been recommended, and uncontrolled and isolated observations have too often guided opinion” (Evans and Hoyle 1933, p. 311). It is unclear exactly what motivated their study,3 but they stated concerns with both “natural variations” in the course of the disease, and with the likelihood that “mental suggestion” could add “bias” in favor of a positive response to a medication (ibid, pp. 313, 316, 334, 335). As such, and admittedly focusing more on the former concern while setting the precedent for decades of studies to follow, they employed in their study of multiple purported anti-anginal drugs a crossover design in which patients were exposed for periods of time to the active drug or to placebo (one of several mixtures of sodium bicarbonate, gentian, +/- liquor carmine; ibid, 313). They found that with one exception, “a measure of improvement appear[ed] to result from every remedy tried, and at least as great an improvement during treatment with placebo,” with placebos yielding a 37.5% overall chance of improvement (ibid, pp. 336, 317).

Harlow Brooks likely spoke for those who were uninspired by such studies. Not only did he (perhaps surprisingly) consider that “suggestion and autosuggestion” were irrelevant to “true angina pectoris,” but swiping at the very aspiration to controlled studies of angina, Brooks observed that the “syndrome does not permit of a standardized scientifically based treatment, for the individual patient is not standardized but is a very pleomorphic biological and emotional integer” (Brooks 1935, pp. 447, 443). Yet others, appreciative of the subjectivity of the experience and reporting of anginal symptoms, were more impressed (Levy 1934). At Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, Arthur Master could already report by 1935 that he and his team at their “special anginal syndrome clinic” had “fully corroborated” Evans and Hoyle’s findings (Master 1935, p. 880). However, while Evans and Hoyle focused a good deal on natural variation as a confounding issue, Masters and his team focused far more on suggestion. Continuing their study, and finding their own placebo, milk sugar, useful to some degree 52% of the time, they concluded in 1939: “It was not a particular drug, but merely the factor of receiving a medication, that gave relief. … Obviously one cannot ascribe a specific effect to a drug when its action is no better than that of an inert substance. The improvement noted must depend on psychological factors” (Master, Jaffe, and Dack 1939, p. 777). Such psychological factors – “the nervous makeup and emotional status of the patient” – were not incidental (ibid, p. 780). On the contrary, they were of “paramount importance,” to the point that “a new medication, a new physician, a new type of therapy may bring relief” (ibid). Indeed, at their clinic, “the average patient feels improved during the first few weeks of attendance … no matter what drug he receives” (ibid, pp. 780-781). That was the (temporary) good news. The flip side was that it likely explained “the reports of good results with numerous drugs” (ibid, p. 781). As a final display of pharmaceutical skepticism and patient concern, they concluded: “It is the physician who spends half an hour talking to a patient gaining his interest and confidence who is most apt to help the patient” (ibid).

Perhaps the most visible display of such skepticism, however, appeared in Harry Gold’s, Nathaniel Kwit’s, and Harold Otto’s use of the “blind test” (quote in the original) to evaluate the xanthines in particular (Gold, Kwit, and Otto 1937, p. 2178). Gold’s team, throughout the middle of the twentieth century, would be largely based in the Department of Pharmacology at Cornell University Medical College, and the cardiology units at New York’s Beth Israel Hospital and Hospital for Joint Diseases (though Gold would hold affiliations with a number of other clinics and hospitals throughout this time). Claiming in 1937 that their study had already been in progress when the Evans and Hoyle paper was published – and apparently continuing while the Master study was ongoing uptown – Gold and his colleagues framed the need for such a blinded study against the backdrop of the multiple factors that could influence a patient’s anginal symptoms (see especially numbers 9 and 10):

- Spontaneous variations in the course of the pain.

- Change in the weather.

- Change of occupation or amount of work.

- Change of diet.

- Change in eating habits with increase in the amount of rest before and after meals.

- Condition of the bowels.

- Emotional stress.

- Change in domestic affairs.

- Confidence aroused in the treatment.

- Encouragement afforded by any new procedure.

- A change of the medical advisor” (ibid, p. 2177).4

After initially hoping to exclude (through a comparison of the response to glyceryl trinitrate versus placebo) a subset of patients especially vulnerable to expectation, Gold and colleagues deserted such a plan, finding that patients across a wide range of clinical severity seemed susceptible (Gold, Kwit, and Otto 1937, p. 2173). And lacking in apparent insight. When patients were asked to “disclose their own belief regarding the influence of the drug,” some “insisted” on the efficacy of the lactose placebo, seemingly justifying “all the circumspection one can exercise in accepting a patient’s judgments in a study of this sort” (ibid, p. 2175). From their study, Gold and colleagues themselves determined “that the xanthines exert no specific action which is useful in cardiac pain” (ibid, p. 2178).

Later in that very issue of JAMA, citing Evans and Hoyle, as well as Gold and his colleagues, the AMA’s Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry would reverse its prior stance and report on the “Limitations of Claims for Aminophylline and Other Xanthine Derivatives” (Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry 1937). And Gold would not only go on to become the foremost advocate for blinding within clinical research more generally, but would become the acknowledged pioneer of “clinical pharmacology” in the United States, with blinding a central component of such rigorous trial methodology. Yet in the domain of anti-anginal evaluation, this was not a simple, linear path, and the shared and differing commitments and findings of various groups from this time are telling.

At one level, patient-blinded crossover studies could still yield diverging results. Several reports from Chicago seemed to favor the use of xanthines, starting with Hyman Massel’s from the Michael Reese Hospital in 1939 (Massel 1939). Across town at Northwestern, George LeRoy, in studying aminophylline, took care to ensure that “like-appearing placebos” were used, dispensed in envelopes and “always designated by number” (LeRoy 1941, p. 923). As he continued: “Care was taken not to discuss with the patient the nature of the drug used. It was felt to be good practice to lead the patient to believe that all the drugs were good.” With this, LeRoy found aminophylline to be far more effective than placebo, and with no “injustice” intended, wondered aloud whether “the poor results with xanthines reported by other workers may well be due to the fact that the patients were attended in hospital or medical school dispensaries with shifting personnels whose diagnostic acuity and criteria varied” (ibid, p. 924). Back at the Michael Reese Hospital, Stephen Elek and Louis Katz, studying papaverine, took pains, in acknowledging the size difference between their larger papaverine and smaller placebo pills, to assure patients “that a small pill may be as potent as a large one by virtue of concentration” so as to offset “any bias that might arise in the patient’s mind because of a difference in size of the two pills” (Elek and Katz 1942, p. 435). Yet in finding in favor of papaverine, they wondered aloud if Evans and Hoyle, in reporting negative results, had simply employed too small a dosage of the medication (ibid, p. 436). In Vermont, Wilhelm Raab extended patient blinding past such vasodilators, studying thiouracil, under the premise (and drawing upon the treatment of angina through thyroidectomy) that the recently-identified thyroxine-suppressing nature of thiouracil might be effective in lowering overall stimulation of the heart and thereby reduce symptoms. Again, while employing a small crossover study that included periods of what he termed “unconscious placebo intake,” Rabb came out not only in favor of thiouracil, but of a reorientation of the understanding of angina around its neurohumoral influences (Raab 1945, p. 252). Thus, patient blinding wasn’t just for skeptics, even as researchers sought to eliminate subjective enthusiasm.

At another level, certain researchers acknowledged such patient subjectivity, but attempted to eliminate it beyond blinding alone. At Boston’s Beth Israel Hospital, another hub of angina research, Joseph Riseman and colleagues (from their own “special clinic” for angina; see Riseman 1943, p. 670) certainly acknowledged the subjective component of anginal pain. Even after attempting to exclude from study those “patients with financial, domestic or social difficulties which were important factors in precipitating attacks,” and while taking care to disguise their “inert” placebos (and to disguise repeat administration of the active drugs through sugar-coating them or painting them with tincture of cudbear), Riseman’s group still found that several patients “felt better with every drug administered.” This led the clinicians to believe that “the improvement apparently consisted of a sense of well-being, induced not by specific medication but by the fact that medical supervision was being given” (Riseman and Brown 1937, pp. 101, 102). Yet Riseman and colleagues felt that they could go beyond Evans, Gold, and their studies by substituting for subjective reporting an “objective” test, namely a standardized exercise-tolerance test, with electrocardiographic monitoring. Here, and still through pharmacologically blinded studies, they found that certain medicines (including several of the xanthines) seemed more effective than placebo in terms of exercise tolerance. For them, the real-world environment of the patient could not be adequately “controlled or observed by the patient,” and thus the exercise-tolerance test made it possible to “differentiate real improvement due to therapy and apparent improvement unrelated to it.” As Riseman concluded, aspiring to a mechanical objectivity that itself dated back to the 19th century: “Objective measurements are essential” (Riseman 1943, p. 672; on “mechanical objectivity,” see Daston and Galison 2010). Notably, however, even in this “controlled” setting, Riseman and colleagues employed patient blinding, though never explicitly discussing the potential for enthusiasm or suggestibility to creep into even such a seemingly decontextualized setting (for much later discussion of the potential for suggestibility to influence exercise treadmill test outcomes, see Benson and McCallie 1979).

Gold and his colleagues took issue with both the outcome measured and the very decontextualization that Riseman was attempting with the exercise-tolerance test. With respect to the former, Gold, focusing on the patient’s subjective symptoms, would later note that “the patient’s complaint is clearly pain and not something wrong with his T-wave” (Gold 1949; see also Gold 1941, p. 10). With respect to the latter, the clinical goal was the treatment of patients in their “natural habitat,” where “the total distress expressed as pain depends not alone on the intensity of the pain perception but on feeling states that may exist or may be aroused by factors associated with the pain perception, such as anxiety, frustration, fear, and panic” (Greiner et al. 1950, pp. 152, 151). As Gold and his colleagues continued: “There is interaction between pain perception and such feeling states, each possessing the power to diminish or intensify the total experience expressed as pain. In the usual exercise tolerance tests in which the exertion is carried out in a special environment under artificial conditions, and with concentration on a particular set of rules, the patient’s usual attitude toward his illness may well be erased” (ibid, p. 151). Patient blinding seemed to level the specific playing field concerning suggestion and the impact of the receipt of medication on pain perception; but further control of the environment ran the risk of conflating the artificial world of the investigator with the real-life world of patients and their subjective symptoms.

The Path to the “Double Blind”

But critically, if Gold favored limits in controlling for patient context, he attempted to extend the rigor of clinical evaluation by focusing on a second component of the patient:clinical researcher dyad – namely, researcher enthusiasm and bias in administering interventions and especially in recording the results. As a gauge of prevailing sentiment, in George LeRoy’s 1941 evaluation of papaverine, while LeRoy was proud of being the consistent, dedicated “one observer” making all the interventions and evaluations in his placebo-controlled study, he admitted that he knew which patients were receiving which remedy. Though he “attempted to be as non-committal as possible,” LeRoy acknowledged that “discerning patients may well have seen my enthusiasm for these particular xanthine drugs” (LeRoy 1941, p. 924). Likewise, pointing to the possibility for both patient and clinician bias, Riseman would remind his own readers in 1943 that “the clinical evaluation of the benefit of therapy is, in fact, the physician’s impression of the patient’s opinion of the response to treatment” (Riseman 1943, p. 672). For Riseman, the solution to such potential bias was the “objective” nature of the exercise-tolerance test. For Harry Gold and colleagues, it would be the blinding of the researcher.

Gold had first employed researcher blinding in a study published in 1935 of varying formulations of ether (Hediger and Gold 1935). As he would later recount, in the context of the Great Depression the question of whether (less expensive) ether out of multi-usage large drums was as effective as ether from small cans held important economic consequences. Conventional opinion was mixed, so Gold proposed in 1933 to put the question to the “blind test” (quotes in original), with the administering anesthesiologists “unaware of the source of the specimens except in terms of code numbers or letters” (Gold 1933), and those (presumably Gold and his colleagues) assessing the outcomes kept similarly in the dark (Gold and Gold 1935). As Shapiro and Shapiro have written, it is unclear whether Gold, by invoking the “blind test,” was referring back to renowned pharmacologist Torald Sollman’s own earlier usage of the term, to the contemporary Old Gold cigarette “Take the Blindfold Test” marketing campaign (as Gold’s colleague, Nathaniel Kwit, suggested decades later), or some other source (Shapiro and Shapiro 1997; Sollman 1917; idem 1930; Advertisement 1928).5 Regardless, Gold found no difference in efficacy between the two sources of ether and would become the world’s leading proponent of researcher blinding as “a simple expedient which insures a record free of subconscious bias” (Gold 1941, p. 8).

For the “blind test” of the efficacy of xanthines in angina, the 1937 published paper reports that in eliciting symptoms from patients, “to eliminate the possibility of bias, the questioner usually refrained from informing himself as to the agent that had been issued until after the patient’s appraisal … had been obtained” (Gold, Kwit, and Otto 1937, p. 2175). Yet “usually” belies a more complicated evolution of the study. As Arthur Shapiro uncovered through interviews with Gold and Kwit, the study had begun in 1932 (a year before the ether study would be planned) with only patients blinded. However, within a few years of running the extensive study, Gold and his colleagues determined that the informed researchers were asking “leading questions” in determining the efficacy of the remedies. Thus, by the end of the study, it appears that the investigators had changed course to ensure that the evaluating clinicians were in the dark regarding what a given patient received. Double-blinding had been brought to angina evaluation, if not yet named as such (Shapiro and Shapiro 1997).6

Over the next decade, Gold would continue to modify the name of such double-blinding, all the while promoting its utility. In a 1943 talk on the “Treatment of Cardiac Pain,” in somewhat revisionist fashion, he noted of the xanthine study that “our experiments were made with both eyes blindfolded; the patient didn’t know what he was getting, and the doctor didn’t know what he was giving” (Gold 1943). Critiquing studies of androgens as vasodilators during the same talk, he reported: “I am not in the slightest degree impressed with these results. The studies were not made with the double-eye blind test.” By January of 1947, in the notes for a talk at the New York Academy of Medicine on “Recent Advances in Therapeutics,” we see what appears to be Gold’s first invocation of “the double-blind test,” to critique the absence of such rigor in evaluations of antihistamines (Gold 1947). This was followed, in a withering March 1948 critique of papaverine for cerebral vasospasm, by a slight modification of the term – now “double blind-test” – and continued skepticism (Gold 1948).

By that year, while the name of the methodology was still in flux, Gold and his colleagues had further refined their technique. In a favorable study of intravenous aminophylline for exertional angina, they reverted to prior nomenclature in reporting that “the study was conducted by the ‘blind’ method.” In particular, “the materials for injection, 10 c.c. of a 2.4 per cent aminophylline solution and an identical quantity of physiologic saline, were prepared by a nurse, for each day, in identical syringes marked only with code numbers so that the contents were unknown to the observer as well as to the subject” (Bakst et al. 1948, p. 529).7 As further evidence of the efforts taken to ensure such blinding, they continued: “A method was devised for varying the order of the trials [no injection versus saline versus aminophylline] so that all possible combinations of the three tests were used in different sequence. The code numbers on the syringes indicated the order in which the injections were to be given. The contents of the syringes and the corresponding code numbers were noted on cards, sealed in envelopes, and kept sealed until the entire study was completed” (ibid).8

Two years later, Gold’s team published their crossover evaluation (Greiner et al. 1950) of the vasodilator khellin (dimethoxy-methyl-furano chromone). Gold would later (Gold 1952) characterize this as the first true “clinical pharmacology” study, approximating the rigor of the laboratory investigation, with objective measurement of symptoms recorded in a seemingly novel “daily report card” system, and rigorous blinding of both patients and researchers. Such blinding required a large team, with different members playing their coordinated but independent roles. From one end, as they noted: “One person received the ‘daily report cards,’ decided on changes in dosage and dispensed the supply of tablets with directions for their use. He knew what the patient had been taking but this knowledge played no part in the record of the results, for his function was neither to question patients regarding the effect of the tablets nor to record judgment; he merely assembled and filed ‘daily report cards’” (Greiner et al. 1950, pp. 144-146). At the other end were the examiners, questioning patients “under conditions of the ‘double blind test’ in which neither the physician nor the patient knew at the time whether the evaluation related to the placebo or khellin” (ibid, p. 146). This August 1950 appearance seems to have been the first published invocation of the term “double blind.”9

The khellin study became an extended opportunity to emphasize the necessity of observer blinding. Holding up LeRoy as a cautionary example, Gold and colleagues publicly noted that an “evaluation of the physician’s enthusiasm (positive suggestion) on the angina of effort would be a study of some interest in itself but it seems self-evident that the physician’s enthusiasm is inadmissible in a scientific experiment” (ibid, p. 153). Privately, and perhaps still stinging from LeRoy’s intimation that earlier, negative studies of xanthines may have stemmed from hospital personnel with variable “diagnostic acuity,” Gold noted to himself: “He knew what the drugs were and he apparently communicated that knowledge to his patients. It was not a true blind test” (Gold undated a). The khellin paper, featuring such then- and future stars of clinical pharmacology as Gold, Kwit, McKeen Cattell, Janet Travell, Theodore Greiner, and Walter Modell, likewise became an opportunity to discuss and show by example the broader requirements for methodological rigor. For instance, whether a given patient would first receive placebo versus khellin was determined by a “randomized” process, in which half received khellin first, the other half placebos (Greiner et al. 1950, p. 146). Concerns over the pitfalls of premature analysis were revealed in self-reflective fashion, with an admission of their own eagerness for an early answer, and their initial consideration of khellin as seemingly effective from this partial analysis, a conclusion that would be overturned by their full study (ibid; for the premature positive reporting on khellin, see (Gold 1949)). Extending their gaze outward, the comments section was taken up with an extended critical discussion of prevailing forms of studies, including the pointed critique of what was seemingly “still the most prevalent, namely, the one in which the patient receives the drug and returns after a week or two with a verbal report on impressions” (Greiner et al. 1950, p. 152). As they concluded: “This is probably evaluation at its worst.”

The khellin crossover angina study would be paralleled and followed by two additional double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, of alpha tocopherol and heparin, respectively (Travell et al. 1949; Rinzler et al. 1953). For the first time among Gold and his team’s angina studies, the crossover approach would be replaced by matched-pair randomization (in which patients were first “matched” to one another by pre-established criteria, and then randomized within pairs to either the active or placebo control group). With the insufficiency of the crossover approach predicated on concern for the long-term storage of alpha tocopherol in the body, and for the impact of changing “environmental” and “seasonal” factors in the heparin study, the two studies represented some of the earliest uses of such matched-pair randomization in the medical literature (Welsh, Podolsky, and Zane 2022). While Janet Travell (who would later garner additional fame as the first female Presidential physician, serving as physician to John F. Kennedy), during the planning and early implementation phases of the heparin study, referred to the “double blind technic” and “double blind method” to be employed, she and her co-authors referred in the published paper in April 1953 to the “double blindfold method” (Travell to Gold 1952; Travell 1952; Rinzler et al. 1953).

Terminology was clearly still being stabilized, and Gold, Travell, and their colleagues would display some ambiguity concerning what exactly constituted a “double-blind” study. In the 1950 khellin paper, this referred not to the clinician administering the treatment (though such clinicians would not be involved in the evaluation of patients), but solely to the patients and evaluators. By the time of the 1953 heparin paper, however, Travell and colleagues would note that the “double blindfold method … meant the study was conducted by a team, and that not merely the patients but also the physicians who questioned and examined them, injected the solutions and later assessed the data were unaware of the nature of the coded solution given to any particular patient” (Rinzler et al. 1953, p. 439). Such enduring ambiguity in the usage of “double blind” has persisted into the twenty-first century (Schulz, Chalmers, and Altman 2002), but it would indeed be “double blind” (or “double-blind”) that would stick as a term itself.10 By 1954, Gold would use a Cornell Conference on Therapy to declare: “The whole history of therapeutics, especially that having to do with the action of drugs on subjective symptoms, demonstrates that the verdict of one study is frequently reversed by another unless one takes measures to rule out the psychic effect of a medication on the patient and the unconscious bias of the doctor. The double-blind insures this” (Gold 1954, p. 724).

Clearly, Gold and his colleagues had been interested in using rigorous clinical studies to shift practices concerning angina. They may have been motivated by experiences like that at another of the Cornell Conferences on Therapy, in 1946, when, after asking legendary cardiologist Harold Pardee whether the suggested impact of a xanthine was not “simply [that of] a placebo,” Pardee responded that despite placebo-controlled studies, he had “seen things happen which made me think that the drugs are really active” (Cornell Conferences on Therapy 1946, p. 298). And, as late as 1950, Gold and his colleagues could lament that despite the efforts of critical investigators from Evans and Hoyle onward, the “survival qualities” of seemingly ineffective remedies like the xanthines was impressive, a tribute not only to “the urgent need of patients for relief and the want of effective measures with which to supply it,” but to the fact “that experience indicating beneficial effects has on its side the force of suggestion, and that the methods employed in the investigation of these agents may not have been sufficiently free from defects to carry complete conviction” (Greiner et al. 1950, p. 151).11 By the late 1950s, however, and after nearly a quarter century of effort to shift the evaluation of anti-anginal therapeutics, Gold and his colleagues could seemingly claim victory, if narrowly defined. As they noted, “nowadays it is a rare study of coronary vasodilators that does not specify control with placebo and ‘double blind’ evaluation of cardiac pain” (Greiner, Bross, and Gold 1957, p. 244). Yet as they realized, this was only a partial victory: “In other areas of therapeutics, the majority of studies are so poorly designed that their data contain no indication as to the correctness of the conclusion” (ibid). Gold had his sights set beyond anti-anginals.

The Double Blind and the Rise of “Clinical Pharmacology”

Much as Gold the cardiologist was using the double-blind to examine the treatment of angina, Gold the “clinical pharmacologist” was using such angina studies to transform clinical evaluation more generally, especially around double-blinding. Not everyone was convinced of the necessity or even legitimacy of double-blinding. As Gold would lament by the late 1950s, “doctors seem to have little difficulty accepting the power of suggestion as applied to the patient.” However, “the notion that the same applies to the doctor has not had an equally cordial reception.” As Gold expanded: “Among the many reasons is the feeling that this requirement impugns their personal integrity, that it is an accusation rather than a point of fact that bias is a normal function of the mind, which may be mostly unconscious, and beyond the investigator’s control” (Gold 1959a, p. 41).12 Other would-be investigators simply could not believe the null results they received through the implementation of the double-blind method. One New York clinician-researcher, writing in JAMA in 1955 and refusing to accept the null answer he received through a double-blinded study, defaulted to the notion that “the future of a drug depends on what it can do in the hands of the general practitioner and not what it should do on the basis of experiments” (Batterman 1955). Gold was not the only one to scoff at such a seeming reversion to the play of biased impressions (Gold 1959a, p. 42). As a University of Miami clinician-researcher replied in JAMA, the very “validity of the scientific method as applied to medicine” was at stake in such deliberations (Ross 1955).

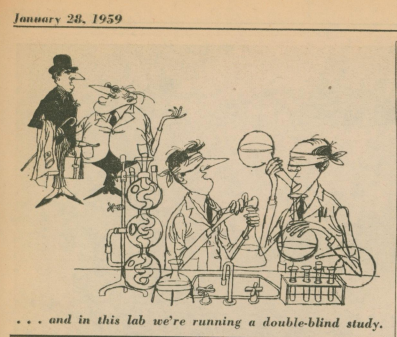

Despite such resistance, Gold was remarkably successful with respect to increasing attention to and usage of the double blind. As Shapiro and Shapiro have somewhat impressionistically written, “interest in the placebo effect and the double-blind procedure increased in the late 1950s, resulting in an avalanche of meetings, symposia, papers, and books” (Shapiro and Shapiro 1997, p. 154). A PubMed search (accessed on 27 July 2022) reveals 78 English-language articles with “double blind” in the title by 1960. The New England Journal of Medicine would publish 36 uses of the term by that time, with its first two in quotes, and two in titles, including regarding its usage in Leonard Cobb and colleagues’ sham-controlled internal mammary artery surgical ligation study of the treatment of angina (Cobb et al. 1959; by 27 July 2022, when this search was conducted, there had been 3643 uses of the term in the journal, including within 73 titles between 1957 and 2012). Double-blinding would indeed be discussed in the “avalanche” of American and British books and symposia devoted to clinical trials by the 1950s and early 1960s (see, e.g., Cole and Gerard 1959; Lasagna and Meier 1959; Laurence 1959; Hill 1960; Mainland 1964).13 By 1959, it had become the subject of a medical cartoon (Cartoon 1959; see figure 1). By 1960, it had become the title – and the central theme and ethical dilemma – of a popular British novel, in which (perhaps hearkening back to Arrowsmith) a clinician scientist applies the double-blind method (so as “to eliminate unconscious bias when testing out a drug”) on an active vaccine treatment for encephalitis in a British island colony (Shapiro and Shapiro 1997, p. 155; Wilson 1960, p. 12). Perhaps indicative of the seeming obviousness and ubiquity of both the term and methodology by 1960 – and of the capacity for historical foreshortening amidst such ubiquity – the novel and clinical trial itself takes place in 1950, by which time, the author mistakenly writes of double-blinded trials: “It was a standard experimental method, and there were no doubt hundreds of trials going on throughout the world on the same basis. There was no need to make a drama out of it” (Wilson 1960, p. 113).

Figure 1. Source: Medical News: A Newspaper for Physicians, 28 January 1959; as also found in Box 17, ff 42, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

And yet, by the late 1950s, Gold and his colleagues were moved to point out that the double blind technique was not “magic,” and could not otherwise “convert a poor experiment into a good one” (Gold 1959, pp. 42-43; on “magic,” see also Modell and Houde 1958, p. 2191). Janet Travell intended in late 1959 to write an article entitled the “Use and Abuse of the Double-blind Method” (Travell to Herrick 1959; it does not appear she wrote the article), while Walter Modell and Raymond Houde, in their AMA Council on Drugs-authorized 1958 report in JAMA, would caution: “A large number of papers emphasize in the very title that this type of control [the double blind] was used, not only as if the use of a control in a clinical experiment were worthy of special mention, but also as if to warn the reader in advance that a special type of insurance had been taken out to guarantee that the results about to be recounted were beyond reproach” (Modell and Houde 1958, p. 2191). Instead, pointing to the discrepant results that could still be derived depending on the variable quality of the rest of the research methodology employed, they warned: “No simple device such as the double-blind technique will correct astigmatism or myopia in the examination of drugs. The blind will not lead the blind to a valid conclusion unless the method somehow also provides vision” (ibid).

Rather, the double-blind was to be one component – albeit a central one – of “clinical pharmacology.” As early as in 1945, while ostensibly speaking on “the pharmacologic basis of cardiac therapy,” Gold had his sights set on broader evaluation and on elevating the status of the evaluation of remedies in people vis a vis seemingly more fundamental science. As he offered: “The term ‘clinical study’ doesn’t rate very high in scientific circles … but there is a vast area of pharmacologic investigation which may be developed with the human subject and which, if the experiments are suitably designed, may be counted on to yield important facts in a manner which complies with the strictest demands of scientific evidence” (Gold 1946, p. 547). Within two years, Gold would be named Professor of Clinical Pharmacology at Cornell, with clinical pharmacology expected to approach the rigor of laboratory and animal investigation, and to be juxtaposed to “therapeutics,” which represented more art than science (Gold 1959a, p. 47; see also Gold 1958). As Gold reported to the New York Academy of Medicine in 1949: “I am inclined to believe that something more than nomenclature is involved. In the pharmacology laboratory, methods for planning and executing investigations on drugs have made great advances, and these are notable by their absence in most clinical studies on drugs” (Gold 1949). As he continued: “I recall a striking illustration in a recent series of papers. There was the most marked contrast in the criteria for scientific evidence made by one and the same investigator, a distinguished pharmacologist, working with one and the same drug, at one time in animal pharmacology, and at another time working on the same problem in humans in collaboration with a clinician. In the case of the human subjects, the laws of scientific evidence seemed to have been completely suspended.” As such, there was a pragmatic rationale to “cultivating the term, clinical pharmacology … as assurance, however feeble it may be, that the investigations may be bound by methods and laws which apply in pharmacology.”

By 1954, the nation’s first Division of Clinical Pharmacology would be launched at Johns Hopkins and led by Louis Lasagna (Lasagna 1961). And by 1957, Gold (who by this time was beginning to use “human pharmacology” interchangeably with “clinical pharmacology,” though it would be “clinical pharmacology” that would stick) felt the time had come for a journal devoted to clinical pharmacology, as he wrote to Walter Modell (Gold 1957; on “human pharmacology,” see Gold 1959a, p. 47; Greiner et al. 1959). Yet Modell’s journal, begun in 1960, would be entitled Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, and such tensions concerning the relative roles of pharmacology, empirical studies of therapeutic outcomes, and the application of such findings in the clinic would apparently continue to play out through the formation of the American College of Clinical Pharmacology and Chemotherapy in 1963, its amalgamation with the American Therapeutics Society to become the American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics in 1969, and the consequent splinter formation of the American College of Clinical Pharmacology that same year (Modell 1960; idem 1962; Gold 1967; idem 1971; Ingenito 1994). Yet despite such internal tensions, by that very year, as the FDA attempted in 1969 to formalize the notion of the well-controlled clinical trial, the double-blind, placebo-controlled method would be encoded as part of the ideal clinical study, unless there were clear reasons not to include it (Podolsky 2015). By the time Harry Gold died in 1972, no fewer than 144 papers would be published in English that year with “double blind” in their title (as accessed on PubMed on 27 July 2022). It had indeed become “a standard experimental method.”

Enduring Blind Spots

Gold was well-attuned to threats to the internal validity of controlled clinical trials, as evidenced, for example, by his expenditure of effort regarding the proper appearance and taste of active and placebo tablets so as to ensure adequate patient blinding (Gold et al. 1949; Gold to French 1949ab; Gold and Gluck 1949). Yet he appears to have been less reflective concerning the academic-industrial relationships through which such studies and their results were funded, conducted, and disseminated. Dominique Tobbell has examined the manner by which the emerging discipline of clinical pharmacology – dramatically underfunded and undermanned in relation to the number of drugs emanating from the post-World War II pharmaceutical industry – accommodated itself from the mid-1950s onward to the pharmaceutical industry (Tobbell 2012). This not only entailed seeking funds for its programs, but manifested in joint efforts with respect to both pushing back against potential threats (as with enforced informed consent) to the research enterprise and concerning the seeming “education” of physicians regarding pharmaceuticals. Gold’s relationship to the pharmaceutical industry in these respects prefigured or paralleled many of these accommodations, and I’ll focus here on the informational ecosystem emerging from double-blinded trials and clinical pharmacology.14

This is not to paint a picture of uniform industry resistance to attempts to tame the marketplace, let alone of a uniform attempt to undermine the results of negative blinded trials. Joseph Gabriel has demonstrated Parke-Davis’s support of the iconic blinded (and negative) trial of sanocrysin starting in 1926; and one of the most impassioned pleas in the medical literature in the 1950s for the uptake of the double blind came from the Department of Clinical Investigation at Upjohn, appearing in JAMA the same month that the negative double-blinded study of Upjohn’s heparin for angina was being reported in the American Journal of Medicine (Gabriel 2014; Hailman 1953; Rinzler et al. 1953). Similarly, as a member of Searle’s Division of Clinical Research wrote in 1954 to Gold upon hearing of the latter’s negative study of their potential diuretic: “I must say that I was disappointed with the results but nevertheless one has to accept these trials” (McKeever to Gold 1954).15

And yet, Gold himself was well aware of the role of industry in promoting the “survival qualities” of seemingly ineffective drugs. This was especially evident in relation to khellin – the subject of his own first truly “clinical pharmacological” study – in which certain industry staffers tried to either discredit or reinterpret the results, while one company seemed to entirely ignore Gold’s team’s study (while only citing positive reports) in its promotional literature concerning its commercial khellin product (Tainter to Gold 1950; Gold to Tainter 1950; Greiner 1951; National Drug Company undated). On the opening page of this promotional brochure Gold handwrote: “No mention of our paper only positive papers” (National Drug Company undated).

Despite such experience, Gold saw a central role for the pharmaceutical industry in the postgraduate education of physicians. Amidst Estes Kefauver’s hearings into the pharmaceutical industry, and at the same time that Charles May was decrying the blurred lines between pharmaceutical promotion and physician education (May 1961), Gold nonetheless proposed: “The pharmaceutical group must add to their program what I believe is inevitable, Post-Graduate Education. … [Industry] has things to teach and a method of communication with the practicing doctor which is unique and vital for good medical practice” (Gold to Winter 1961). This could especially entail, in anticipation of the expansion of reliance on “key opinion leaders” to come, the industry funding of seemingly neutral “qualified investigators or teachers to meet with practicing physicians at a more local level than is ordinarily accomplished by the big national (or even regional) investigative or clinical meetings” (Gantt to Gold 1960).16 Such tensions between pharmaceutical promotion and physician education – and especially concerning the role of industry in “educating” physicians – would persist for decades to come (Greene and Podolsky 2009).

Still more fundamentally, Gold appears to have had certain blind spots concerning the political economy of knowledge production by the emerging discipline of clinical pharmacology. In 1957, he and his colleagues reported on their double-blinded study of laxatives for constipation. Invoking the image of the epistemically and morally dubious “testimonial,” they noted that such humble preparations were chosen for study not for their representing the apogee of clinical or industrial pharmacology, but for being “supported by the weakest series of studies” while representing the largest sales volume of any class of drugs (Greiner, Bross, and Gold 1957, p. 244). Finding some laxatives better than placebo, and others not, Gold and colleagues were admittedly less concerned with the consistency of stool than with ensuring the consistency of clinical investigative methodology. As they stated: “This presentation neither defends nor deplores the widespread use of laxatives by the public. Its concern is with methods for measuring the action of drugs in human patients. Laxatives are relevant only as a class of drugs sorely in need of the application of pharmacologic principles in their clinical trials” (ibid, 252). Pointing explicitly to the “placebo effect, a shorthand way of saying that the patient’s psyche induces responses to the doctor’s interest and prescriptions,” Gold and his colleagues again emphasized that “the physician’s psyche, too, may alter drug response by the unconscious attitudes imparted to the patient before the drug is taken and when the drug effects are being assessed” (ibid, pp. 252-253). This all warranted a double-blind study conducted by a “team” of physicians (ibid, p. 253).

As it would turn out, Gold was not the only clinical pharmacologist invoking the specter of the “testimonial” that year. Harvard infectious disease specialist Maxwell Finland was similarly invoking the “testimonial” as pertaining to the dubious testing and marketing of certain emerging antibiotics, arguing for the need for “controlled clinical studies” to tame the therapeutic marketplace and helping set in motion a path that would lead to the passage of the Kefauver-Harris Amendments in 1962 (mandating proof of drug efficacy by “well-controlled studies”), and the regulatory defining of the “well-controlled” study in terms of the randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study by 1969 (Podolsky 2015).

There are certain historical ironies to such outcomes. Gold and colleagues, in their laxative paper, pointed to the economic waste of inefficacious remedies making it to the marketplace, and the potential capacity for “physicians with a mild inclination toward research [to] apply such [clinical pharmacological] methods within the structure of their own practice, break the ‘bottle jam’ on the pharmaceutical shelves, return most of these unknown compounds firmly and securely to laboratory limbo, and retain the few that offer particular promise” (Greiner, Bross, and Gold 1957, p. 254). Perhaps Gold, who had long emphasized the complex, team-based notion of rigorous clinical research, should have known better. This rigorous approach, soon inscribed into the Kefauver-Harris Amendments and their aftermath, would create economic barriers to the conduct of such broadly disseminated research (Greene and Podolsky, 2012). Instead, the chief source of funding for such team-based studies would eventually be the pharmaceutical industry itself (Bothwell et al. 2016). While the shape of individual studies could conform to such rigorous methodological prescriptions, the shape of the overall marketplace would increasingly bear the impress of commercial industry needs and choices regarding which agents to study. Blinding at the level of the patient and investigator could only accomplish so much.

Acknowledgments:

I’ve benefitted greatly in conceiving and writing this paper from the insights and feedback provided by Iain Chalmers, David Jones, Ted Kaptchuk, and Nick Rasmussen. I’m also grateful to Nicole Milano and Tali Han at the Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell for their efforts in making the Harry Gold papers available for examination.

This James Lind Library article has been republished in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 3 parts.

Podolsky S. The (Harry) Gold standard: angina, suggestion and the path to the ‘double-blind’ test and clinical pharmacology. Part 1: angina relief and suggestion. JRSM 2023;116:246-251

Podolsky S. The (Harry) Gold standard: angina, suggestion and the path to the ‘double blind’ test and clinical pharmacology. Part 2: the path to the ‘double blind’. JRSM 2023;116:274-278

Podolsky S. The (Harry) Gold standard: angina, suggestion and the path to the ‘double-blind’ test and clinical pharmacology. Part 3: the double blind and the rise of ‘clinical pharmacology’ JRSM 2023;116:307-313

References

Advertisement (1928). Presenting … Charlie Chaplin in the Blindfold Cigarette Test. New Yorker, 23 June 1928, p. 45.

Aronowitz RA (1998). Making Sense of Illness: Science, Society, and Disease. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Askanazy S (1896). Klinisches über Diuretin. Deutsches Archiv für Klinische Medicine 56: 209-230.

Bakst H, Kissin M, Leibowitz S, Rinzler S (1948). The Effect of Intravenous Aminophylline on the Capacity for Effort without Pain in Patients with Angina of Effort. American Heart Journal 36: 527-534.

Batterman RC (1955). Appraisal of New Drugs [Letter to the Editor]. JAMA 158: 1547.

Beecher HK (1952). Experimental Pharmacology and Measurement of the Subjective Response. Science 116: 157-162.

Benson H, McCallie DP (1979). Angina Pectoris and the Placebo Effect. NEJM 300: 1424-1429.

Bothwell LE, Greene JA, Podolsky SH, Jones DS (2016). Assessing the Gold Standard: Lessons from the History of RCTs. NEJM 374: 2175-2181.

Brandt AM (2007). The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product that Defined America. New York: Basic Books.

Brooks H (1935). The Treatment of the Patient with Angina Pectoris. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 11:442-452.

Cartoon (1959). Medical News: A Newspaper for Physicians, 28 January 1959, as also found in Box 17, ff 42, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Cobb LA, Thomas GI, Dillard DH, Merendino KA, Bruge RA (1959). An Evaluation of Internal-Mammary-Artery Ligation by a Double-Blind Technic. New England Journal of Medicine 260: 1115-1118.

Cole JO, Gerard RW, eds. (1959). Psychopharmacology: Problems in Evaluation. Washington, D.C. National Academy of Sciences – National Research Council.

Cornell Conferences on Therapy (1946). Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease. American Journal of Medicine 1: 291-300.

Cornell Conferences on Therapy (1954). How to Evaluate a New Drug. American Journal of Medicine 11: 722-727.

Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry (1930). Therapeutic Claims for Theobromine and Theophylline Preparations. JAMA 94: 1306.

Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry (1937). Limitations of Claims for Aminophylline and Other Xanthine Derivatives. JAMA 108: 2203.

Daston L and Galison P (2010). Objectivity. New York: Zone Books.

Elek SR and Katz LN (1942). Some Clinical Uses of Papaverine in Heart Disease. JAMA 120: 434-441.

Evans W (1968). Journey to Harley Street. London: David Rendel LTD.

Evans W, Hoyle C (1933). The Comparative Value of Drugs Used in the Continuous Treatment of Angina Pectoris. Quarterly Journal of Medicine 2: 311-338.

Freedberg AS, Riseman JEF, Spiegl ED (1941). Objective Evidence of the Efficacy of Medicinal Therapy in Angina Pectoris. American Heart Journal 22: 494-518.

Gabriel J (2014). The Testing of Sanocrysin: Science, Profit, and Innovation in Clinical Trial Design, 1926-1931. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 69: 604-632.

Gaddum JH (1954). Clinical Pharmacology. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 47: 195-204.

Gantt CL to Gold H (1960). 1 February 1960. Box 4, ff 14, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gilbert NC, Kerr JA (1929). Clinical Results in Treatment of Angina Pectoris with the Purine-Base Diuretics. JAMA 92: 201-204.

Gold H ([inferred though unsigned], 1933). “Plan of Clinical Investigation on Ether Deterioration.” 2 October 1933. Box 16, ff 35, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H (1938). “Concerning Therapeutics [Delivered Wednesday, April 6, 1938, at Queens County Medical Building, Forest Hills, Long Island].” Box 7, ff 9, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H (1939). Drug Therapy in Coronary Disease. JAMA 112: 1-6.

Gold H (1941). Some Recent Developments in Drug Therapy. North End Clinic Quarterly 2: 5-17.

Gold H (1943). “Treatment of Cardiac Pain [Symposium, Post Graduate Hospital, May 4, 1943].” Box 8, ff 26, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H (1946). Pharmacologic Basis of Cardiac Therapy. JAMA 132: 547-554.

Gold H (1947). “Recent Advances in Therapeutics [Friday Afternoon Lecture Series, The New York Academy of Medicine, January 17, 1947].” Box 7, ff 40, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H (1948). “Discussion of the Paper [“Papaverine in the Treatment of Hypertensive Encephalopathy”] by Russek and Zolman [March 23, 1948].” Box 17, ff 38, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H (1949). “Clinical Pharmacology of Cardiac Drugs: 23rd Series of Friday Afternoon Lectures at the New York Academy of Medicine [March 25, 1949].” Box 7, ff 74, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H (1950). “Friday Afternoon Lecture Series, New York Academy of Medicine, February 3, 1950.” Box 7, ff 80, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H (1952). Editorial: “The Proper Study of Mankind is Man.” American Journal of Medicine 12: 619-620.

Gold H ([inferred though unsigned], 1957). “An Argument for a Journal Devoted to Clinical Pharmacology.” 19 December 1957. Box 3, ff 24, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H (1958). “Human Pharmacology [Talk before the Michigan State Medical Society, October 3, 1958].” Box 17, ff 42, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H. (1959a). Experiences in Human Pharmacology. In Laurence DR, ed., Quantitative Methods in Human Pharmacology and Therapeutics: Proceedings of a Symposium Held in London, on 24th and 25th March, 1958. London: Pergamon Press, pp. 40-54.

Gold H (1959b). “Psychological Factors [Notes for a talk on “Planning Clinical Trials” for the 1959-1960 meeting of the American Statistical Association and the Biometric Society].” Box 7, ff 102, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H (1967). Clinical Pharmacology – Historical Note. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 7: 309-311.

Gold H (1971). The American College of Clinical Pharmacology. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 11: 321-322.

Gold H ([inferred though unsigned], undated a). “Angina Pectoris – LeRoy – 1941.” Box 15, ff 16, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H ([inferred though unsigned], undated b). Notes on “Henry K. Beecher, Experimental Pharmacology and Measurement of the Subjective Response; Science, 116; 157, 1952.” Box 17, ff 42, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to Berman E (1962a). 22 October 1962. Box 4, ff 15, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to Berman E (1962b). 7 December 1962. Box 4, ff 15, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to Celebrezze A (1962 [addressee as inferred from Larrick to Gold, 15 October 1962]. 24 September 1962. Box 1, ff 56, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to French CW (1949a). 13 July 1949. Box 14, ff 24, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to French CW (1949b). 16 August 1949. Box 14, ff 24, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to Gantt CL (1960). 23 February 1960. Box 4, ff 14, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to Master A (1949). 11 May 1949. Box 17, ff 7, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to Tainter ML (1950). 27 June 1950. Box 17, ff 4, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to Winter IC (1952). 25 June 1952. Box 4, ff 11, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H to Winter IC (1961). 29 July 1961. Box 4, ff 13, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H, Gluck J (1949). “Memo on Pink Tablet Study.” 15 August 1949. Box 14, ff 24, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H, Gold D (1935). The Stability of U.S.P. Ether after the Metal Container has been Opened: With Preliminary Results of a Clinical Comparison of U.S.P. Ether in Large Drums with Ether in Small Cans Labeled “For Anesthesia.” Anesthesia and Analgesia 14 (1935): 92-95.

Gold H, Greiner T, Rinzler SH, Kwit N, Gluck J, Bakst H, Robbins M, and Weaver J (1949). “Memorandum on Plan for Testing the Adequacy of the Daily Report Card System in Detecting the Difference between a Potent Drug and an Inert Placebo in Angina Pectoris.” 2 August 1949. Box 14, ff 24, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Gold H, Kwit NT, Otto H (1937).The xanthines (theobromine and aminophyllin) in the treatment of cardiac pain. JAMA 108;2173-2179.

Gold H, Travell J, Modell W (1937). The Effect of Theophylline with Ethylenediamine (aminophylline) on the Course of Cardiac Infarction following Experimental Coronary Occlusion. American Heart Journal 14: 284-296.

Greene JA, Podolsky SH (2009). Keeping Modern in Medicine: Pharmaceutical Promotion and Physician Education in Postwar America. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 83: 331-378.

Greene JA, Podolsky SH (2012). Reform, Regulation, and Pharmaceuticals – The Kefauver-Harris Amendments at 50. NEJM 367: 1481-1483.

Greiner TH (1949 [undated, though date inferred from Greiner 1950]). “A Method for the Evaluation of the Effect of Drugs on the Cardiac Pain of Angina of Effort: A Study of Khelin. To be Presented to the Pharmacological Society.” Box 17, ff 4, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Greiner T (1950). A Method for the Evaluation of the Effect of Drugs on the Cardiac Pain of Angina of Effort: A Study of Khellin. [Abstracts of Papers, American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Inc. Fall Meeting, Indianapolis, Indiana, November 17-19, 1949]. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 98: 10.

Greiner T (1951). “Memo to Dr. Gold: Interview with Dr. Robert Tully, Smith, Kline, and French.” 15 January 1951. Box 17, ff 7, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Greiner T, Bross I, Gold H (1957). A Method for Evaluation of Laxative Habits in Human Subjects. Journal of Chronic Diseases 6: 244-255.

Greiner T, Gold H, Cattel M, Travell J, Bakst H, Rinzler SH, Benjamin ZH, Warshaw LJ, Bobb AL, Kwit NT, Modell W, Rothendler HH, Messeloff CR, Kramer ML (1950). A Method for the Evaluation of the Effects of Drugs on Cardiac Pain in Patients with Angina of Effort: A Study of Khellin (Visammin). American Journal of Medicine 9: 143-155.

Greiner T, Gold H, Ganz A, Kwit NT, Warshaw L, Rao N, Fujimori H (1959). “Case Report” in Human Pharmacology: Study of a Series of Pyrimidinedione Diuretics, Including Aminometradine (Mictine) and Amisometradine (Rolicton). JAMA 171: 290-295.

Hailman HF (1953). The ‘Blind Placebo’ in the Evaluation of Drugs [Letter to the Editor]. JAMA 151: 1430.

Hediger EM, Gold H (1935). U.S.P. ether from large drums and ether from small cans labeled ‘For Anesthesia’. JAMA 104: 2244-2448.

Hill AB, ed. (1960). Controlled Clinical Trials: Papers Delivered at the Conference Convened by The Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

Ingenito AJ (1994). American College of Clinical Pharmacology: 25 Year History, 1969-1994. Available at https://accp1.org/pdfs/documents/about/accphistory1969-1994.pdf.

Johnson A (2019). Textbooks and other publications on controlled clinical trials, 1948 to 1983. JLL Bulletin: Commentaries on the history of treatment evaluation (https://www.jameslindlibrary.org/articles/textbooks-and-other-publications-on-controlled-clinical-trials-1948-to-1983/).

Kaptchuk TJ (1998). Intentional Ignorance: Blind Assessment and Placebo Controls in Medicine. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 72: 389-433.

Larrick GP to Gold H (1962). 15 October 1962. Box 1, ff 56, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Lasagna L (1961). The Role of a Division of Clinical Pharmacology in a University Environment. Postgraduate Medicine 29: 525-528.

Lasagna L, Meier P (1959). Experimental Design and Statistical Problems. In Waife SO and Shapiro AP, eds., The Clinical Evaluation of New Drugs. New York: Paul B. Hoeber, Inc., pp. 37-60.

Laurence DR, ed. (1959). Quantitative Methods in Human Pharmacology and Therapeutics: Proceedings of a Symposium Held in London, on 24th and 25th March, 1958. London: Pergamon Press.

LeRoy GV (1941). The Effectiveness of the Xanthine Drugs in the Treatment of Angina Pectoris. JAMA 116: 921-925.

Levy RL (1934). Management of the Patient with Anginal Pain. NEJM 211: 392-397.

Mainland D (1964). Some Statistical Problems in the Planning and Performance of Clinical Trials. In Nodine JH and Siegler PE, eds., Animal and Clinical Pharmacologic Techniques in Drug Evaluation. Chicago: Year Book Publishers, Inc., pp. 27-35.

Massel HM (1939). Clinical Observations on the Value of Various Xanthine Derivatives in Angina Pectoris. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine 24: 380-383.

Master AM (1935). Treatment of Coronary Thrombosis and Angina Pectoris. Medical Clinics of North America 19: 873-891.

Master AM, Jaffe HL, Dack S (1939). The drug treatment of angina pectoris due to coronary artery disease. American Journal of Medical Science 197:774-782.

May C (1961). Selling Drugs by “Educating” Physicians. Journal of Medical Education 36: 1-23.

McKeever WP to Gold H (1954). 9 March 1954. Box 4, ff 11, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Mendel D, Silverman ME (2001). William Evans. Clinical Cardiology 24: 487-489.

Modell W (1960). Editorial. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1: 1-2.

Modell W (1962). Clinical Pharmacology: A Definition. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 3: 235-238.

Modell W, Houde RW (1958). Factors Influencing Clinical Evaluation of Drugs: With Special Reference to the Double-Blind Technique. JAMA 167: 2190-2199.

National Drug Company (undated, likely late 1950). “Ammivin: Pure Khellin – A Potent Coronary Vasodilator.” Box 7, ff 7, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Podolsky SH (2015). The Antibiotic Era: Reform, Resistance, and the Pursuit of a Rational Therapeutics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Raab W (1945). Thiouracil Treatment of Angina Pectoris. JAMA 128 (1945): 249-256.

Rasmussen N (2005). The Commercial Drug Trial in Interwar America: Three Types of Physician Collaborator. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 79: 50-80.

Rasmussen N (2008). On Speed: From Benzedrine to Adderall. New York: New York University Press.

Rinzler SH, Bakst H, Benjamin Z, Bobb AL, Travell J (1950). Failure of Alpha Tocopherol to Influence Chest Pain in Patients with Heart Disease. Circulation 1: 288-293.

Rinzler SH, Travell J, Bakst H, Benjamin ZH, Rosenthal RL, Rosenfeld S, Hirsch BB (1953). Effect of Heparin in Effort Angina. American Journal of Medicine 14: 438-447.

Riseman JEF (1943). The Treatment of Angina Pectoris. NEJM 229: 670-680.

Riseman JEF, Brown MG (1937). Medicinal Treatment of Angina Pectoris. Archives of Internal Medicine 60 (1937): 100-118.

Ross BD (1955). Appraisal of New Drugs [Letter to the Editor]. JAMA 159: 624.

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Altman DG (2002). The Landscape and Lexicon of Blinding in Randomized Trials. Annals of Internal Medicine 136: 254-259.

Shapiro AK, Shapiro E (1997). The Powerful Placebo: From Ancient Priest to Modern Physician. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sismondo S (2013). Key Opinion Leaders and the Corruption of Medical Knowledge: What the Sunshine Act Will and Won’t Cast Light On. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics 41: 635-643.

Sollman T (1917). The Crucial Test of Therapeutic Evidence. JAMA 69: 198-199.

Sollman T (1930). The Evaluation of Therapeutic Remedies in the Hospital. JAMA 94: 1279-1281.

Tainter ML to Gold H (1950). 22 June 1950. Box 17, ff 4, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Tobbell DA (2012). Pills, Power, and Policy: The Struggle for Drug Reform in Cold America and its Consequences. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Travell J (1952). “Memo to Harry Gold: Progress Report of Study of Heparin for Angina Pectoris.” 11 April 1952. Box 5, ff 2, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Travell J to Gold H (1952). 4 January 1952. Box 5, ff 2, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Travell J to Herrick AD (1959). 1 December 1959. Box 5, ff 2, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

Travell J, Rinzler SH, Bakst H, Benjamin ZH, Bobb AL (1949). Comparison of effects of alpha-tocopherol and matching placebo on chest pain in patients with heart disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 52:345-53.

Welsh BC, Podolsky SH, and Zane SN (2022). Pair-matching with Random Allocation in Prospective Controlled Trials: The Evolution of a Novel Design in Criminology and Medicine, 1926-2021. Journal of Experimental Criminology: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09520-2.

Wilson JR (1960). The Double Blind. New York: Doubleday.

Winter IC to Gold H (1955). 30 December 1955. Box 4, ff 12, Harry Gold Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

NOTES

- Note that as indication of the fluidity of the term during its emergence in the 1950s, it remains unclear whether “double blind” should be hyphenated or not. It was not hyphenated in its initial published appearance in 1950, but was hyphenated in Harry Gold’s classic articulation of the method as a key component of clinical evaluation in 1954. In this paper, I will hyphenate it in its adjectival and verb forms, and not hyphenate it in its nominal form (though this admittedly does not follow its usage in the two papers cited). (Greiner et al., 1950, p. 146; Cornell Conferences on Therapy 1954, p. 724).

- “Mit der Sicherheit eines Experimentes verschwanden die Aufälle sofort oder sehr bald nach der Aufnahme der Diuretinbehandlung, und traten ebenso prompt wieder auf, sobald das Mittel ausgesetzt wurde” (Askanazy 1896, p. 224).

- Such origins do not appear in (Evans 1968) or in (Mendel and Silverman 2001). John Gaddum, in his Walter Ernest Dixon Memorial Lecture delivered in 1954, expressed that “this important paper probably owed something to Dixon’s influence, since one of the authors was a close colleague of his” (Gaddum 1954, p. 197).

- Per Arthur Shapiro’s interviews with Gold and Nathaniel Kwit in the late 1960s, the study began in 1932; see (Shapiro and Shapiro 1997, p. 142). For Gold’s later sharing of experimental vasodilatory medications with Master, see (Gold to Master 1949).

- On Old Gold’s use of such clever marketing devices to rise to become the fourth-leading brand of cigarettes by the early 1930s, see (Brandt 2007).

- In the midst of the xanthine study, yet after the ether study, Gold and colleagues likewise applied researcher blinding to an animal study of the impact of aminophylline on experimental coronary infarcts, not showing any benefit when the intervention “was unassisted by the intangible something which is apt to be added by an observer’s unconscious bias” (Gold 1938; see also Gold, Travell, and Otto 1937).

- While Gold was not an author on the article, an acknowledgement noted the Beth Israel Hospital (New York) authors’ “appreciation to Dr. Harry Gold, Chief of the Cardiovascular Research Unit, for his advice and help during the course of this study.” The study was “aided” by a grant from the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry of the American Medical Association.

- The authors also noted: “Whether saline injection alone produces any increase in the capacity for effort, through suggestion or other means, was not determined because the number of suitable tests for such a comparison was too small” (Bakst et al. 1948, p. 533).

- In the notes for a talk on the khellin study at the annual meeting of the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics delivered in November of 1949, Theodore Greiner noted its “double blind” nature. But the term did not appear in the published abstract for the talk. In their published February 1950 study of alpha tocopherol on angina, featuring five of the co-authors from the khellin study, the researchers noted the “doubly blind conditions” under which the alpha tocopherol study was conducted. See (Greiner 1949; idem 1950; Rinzler et al. 1950).

- Outside the Cornell group, Harvard’s Henry Beecher referred to blinding as the “ ‘unknowns’ technique,” which Gold considered to himself “a substitute for our double-blind term.” See (Beecher 1952; Gold undated b). Across the Atlantic, John Gaddum preferred the term “dummy” to “placebo,” while acknowledging in 1954 that such controlling of both subject and research bias was “known in America as a double blind test” (Gaddum 1954, p. 197).

- For an earlier invocation of this rationale, see (Gold 1950). By the end of the decade, Gold would add the inertia of “long years of habitual prescribing based on early and authoritative impressions” as a factor promoting the “survival” of such remedies despite scientific evidence to the contrary (Gold 1959, p. 44).

- In the notes for a talk on “Planning Clinical Trials” for the 1959-1960 meeting of the American Statistical Association and Biometric Society, Gold similarly wrote: “I have known doctors who have taken offense at the notion [of their own bias]. They regard it as an attack on their character; charged with dishonesty. … What they fail to appreciate is that bias is a normal state of the mind, and what is more, most of it is unconscious, ‘I try to be unbiased’[.] The trouble is you cant [sic] try because you don’t realize you are biased. It is unconscious” (Gold 1959b; underlining in the original).

- Mainland would note that at an international seminar on medical records and statistics in 1961, “American and Br1itish speakers emphasized the importance of double-blind trials wherever possible, whereas the general European speakers thought that it was sufficient if the patient was kept in the dark regarding therapy … – an attitude which many of us ‘converts’ [in the United States and Great Britain] possessed not very long ago” (Mainland 1964, p. 28). For the increase in volumes devoted to clinical trial methodology during this period, see (Johnson 2019).

- On funding, see, e.g., (Gold to Winter 1952). Gold’s opposition to informed consent in the early 1960s was both personal (and perhaps related to his comfort with paternalistically keeping patients “in the dark” [“I never did seek consent in the 40 years I have been working in human pharmacology”]) and publicly deployed by him (with some prodding from colleagues in industry) in the early 1960s, especially in relation to the proposed introduction of informed consent (a “snare and delusion,” in Gold’s terms) into what would become the Kefauver-Harris Amendments, with such requirements perhaps watered down in response to his opposition. See (Gold to Berman 1962ab; Gold to Celebrezze 1962; Larrick to Gold 1962; Podolsky 2015). For “in the dark,” see (Cornell Conferences on Therapy 1946, p. 298).

- The following year, Searle’s Director of Clinical Research, admittedly unclear of the mechanism of action of a promising anti-anginal, wrote to Gold that “we are very anxious to see a critically designed ‘double blind’ study of the effectiveness of this agent” (Winter to Gold 1955).

- For Gold’s enthusiastic response to G.D. Searle & Co’s Clarence Gantt , affirming “the essential role of the industry in the field of medical education of the practicing doctor,” see (Gold to Gantt 1960). On the rise of “key opinion leaders,” see (Sismondo 2013).

Podolsky SH (2022). The (Harry) Gold Standard: angina, suggestion, and the path to the “double-blind” test and Clinical Pharmacology.

© Scott H Podolsky, Center for the History of Medicine, Countway Medical Library, 10 Shattuck Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA; Email: Scott_Podolsky@hms.harvard.edu

Cite as: Podolsky SH (2022). The (Harry) Gold Standard: angina, suggestion, and the path to the “double-blind” test and Clinical Pharmacology. JLL Bulletin: Commentaries on the history of treatment evaluation (https://www.jameslindlibrary.org/articles/the-harry-gold-standard-angina-suggestion-and-the-path-to-the-double-blind-test-and-clinical-pharmacology/)

In his seminal history of blind assessment, Ted Kaptchuk traces the history of “intentional ignorance” in medical research from the 18th century skeptical evaluation of mesmerism, through the attachment of double-blinding to the mid 20th century randomized controlled trial as the embodiment of the hard science of clinical medicine (Kaptchuk 1998). Having focused attention on the late 19th century and early 20th century European concern with “suggestion” (and its likely impact on such early 20th century German researchers as Adolf Bingel and Paul Martini), Kaptchuk nevertheless suggests that such concerns regarding suggestion were slow to cross the Atlantic. He thus grounds the Anglo-American interwar incorporation of blind assessment into clinical research not in terms of “continental concern with suggestion,” but rather as “technical organizational problems” (ibid, p. 422).

And yet, Anglo-American studies of the treatment of angina pectoris – the debilitating chest pain considered by then to accompany coronary artery disease – would not only play the key role between the 1930s and 1950s in the formal advent of the “double-blind” study within American clinical pharmacology, but would be grounded from the 1930s onward in concerns over “suggestion” and the impacts of anxiety, context, and the apparently alleviating effect of the act of providing medication itself in the course of the experience and evaluation of anginal pain.

No one would be more central to the ascendance of the “double blind”1 as a key component of angina evaluation, and of rigorous clinical trial methodology more generally, than Cornell clinician and pharmacologist Harry Gold. And Gold saw the double blind as only one methodological component – albeit a crucial one – that elevated therapeutic evaluation beyond mere “clinical trials” to what he termed “clinical pharmacology” (or “human pharmacology”), approximating the rigor of the laboratory and capable of separating pharmaceutical wheat from chaff. Yet Gold, focused on the internal validity of the experiment, was not without his own blind spots concerning the larger therapeutic ecosystem in which such drugs were introduced and evaluated. This paper, with angina and Gold as its focus, situates the advent of the double blind amidst such clinical, academic, and industrial concerns during a crucial period in the history of the controlled clinical trial.

Angina Relief and Suggestion