Abstract

Background: Science is cumulative and should cumulate scientifically. In 1999, we published our first audit of deficiencies in reports of Randomised Control Trials (RCTs) published in five major general medical journals. Over the course of the subsequent 25 years, we conducted five follow-up audits to assess the extent to which new trials had been reported as having been initiated and/or concluded with up-to-date systematic reviews of other relevant trials.

Objective: We wished to assess the extent to which systematic reviews had been used in designing and reporting RCTs in five major general medical journals over the 25 years since our first audit.

Design: We evaluated 175 reports of RCTs published in Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet or New England Journal of Medicine, which had been published in May 1997, 2001, 2005, 2009, 2012 or 2022.

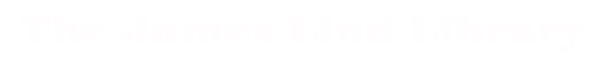

Results: In trials published in May 2022, the Introduction sections of 8.8% (3/34) of reports of RCTs published in the five journals referenced up-to-date systematic reviews that had informed the trial’s design, with a further 52.9% (18/34) mentioning a previous systematic review of other trials in the topic area. In the six audits of trials combined across the 25 years, these figures were 2.9% (5/175) and 31.4% (55/175), respectively.

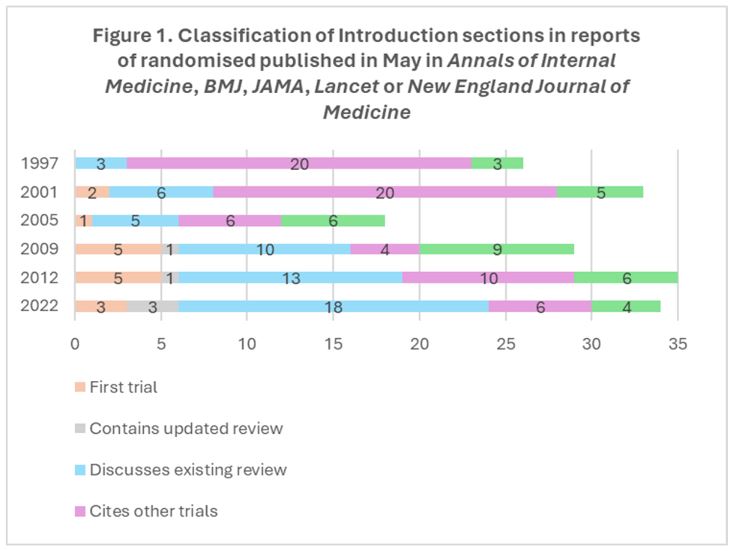

In the Discussion sections of trials published in 2022, the RCT findings were integrated in updated systematic reviews in 2.9% (1/34) of reports and in 50% (17/34) cited previous systematic reviews without integrating the new findings. These figures for the whole 25 years were 3.4% (6/175) and 28.6% (50/175).

Comparing the first and last years of this audit, 11.5% (3/26) of the trial reports published in 1997 used systematic reviews in their Introduction sections compared with 61.8% (21/34) of trial reports in 2022; while 23.1% (6/26) of the 1997 reports mentioned systematic reviews in their Discussion sections compared with 52.9% (18/34) of trial reports published in 2022.

Conclusion: There was a modest increase over 25 years in the use of systematic reviews in designing and interpreting randomised trials reported in five high profile medical journals. Considerable scope remains for setting reports of RCTs in context. Until this deficiency has been addressed by the research community, people are likely to continue to suffer and sometimes to die unnecessarily because of an unreliable evidence base for health care and additional research.

Background

Plans for new research should use systematic reviews of relevant existing research to provide the scientific and ethical justification for the design and conduct of new studies. Updated systematic reviews should be used to place new findings in context and thus provide evidence relevant to informing decisions in policy and practice. This helps to avoid research waste and ensures that users of reports of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) will have ready access to up-to-date accounts of the available evidence on the topics of interest (Chalmers & Altman 1999; Clarke 2004; Glasziou et al, 2014). These principles were promoted in the Explanation and Elaboration document for the 2010 CONSORT statement, which recommends “that, at a minimum, the discussion should be systematic and based on a comprehensive search, rather than being limited to studies that support the results of the current trial” (Moher et al, 2010).

Over a period of 25 years (1997 to 2022), we conducted a series of audits to assess the extent to which these principles were observed in five high profile general medical journals: Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet and New England Journal of Medicine. In the first audit in this series, we concluded by paraphrasing John Donne (Donne): “No trial is an island, entire of itself; every trial is a piece of the continent, a part of the main” (Clarke & Chalmers 1998).

Our first audit showed that only 2 of the 26 reports of RCTs published in our ‘sentinel’ journals in May 1997 included updated systematic reviews in their Discussion sections, although four others mentioned systematic reviews in that section of the reports. (Clarke & Chalmers 1998). Our audit was expanded in 2005 to include assessments of the use of systematic reviews in the Introduction sections of the RCT reports (Clarke et al, 2007). This, and our audits in 2009 (Clarke et al, 2010) and 2012 (Clarke & Hopewell 2013), showed that most reports of RCTs did not use their Introduction sections to mention the use of systematic reviews for trial design or justification.

Methods

We used similar methods to those in our earlier audits to identify reports of RCTs reported in one of the five ‘sentinel’ journals and to determine how systematic reviews were used in their Introduction and Discussion sections (Clarke & Chalmers 1998; Clarke et al, 2002; Clarke et al, 2007; Clarke et al, 2010; Clarke & Hopewell 2013). For this final paper, we assessed the Introduction sections of the reports from 1997 and 2001 to provide a complete dataset for both the Introduction and Discussion sections across the 25 years.

Results

Across the 25 years, we identified 175 reports of RCTs in Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet or New England Journal of Medicine in the month of May in 1997, 2001, 2005, 2009, 2012 or 2022.

The Introduction sections of only 2.9% (5/175) of these reports contained references to up-to-date systematic reviews to inform the design of the new RCT; 31.4% (55/175) mentioned previous systematic reviews in the topic area; 37.7% (66/175) cited other RCTs; and 18.9% (33/175) did not claim to be the first RCT addressing the topic in question and did not contain references to other RCTs or systematic reviews.

In their Discussion sections, the findings of the new RCT were integrated into an updated systematic review in 3.4% (6/175) of reports; 28.6% (50/175) cited previous systematic reviews but did not integrate the findings of the new RCT in them; 12.0% (21/175) claimed to be the first RCT addressing the topic; and the remaining 56.0% (98/175) did not provide information to suggest that any citations for other RCTs arose from a systematic attempt to set the new results in context.

Figures 1 and 2 present the findings for the Introduction sections and for the Discussion sections, respectively, for each of the six audits across the 25 years. Comparing May 1997 and May 2022, the proportion of reports of RCTs mentioning a systematic review in their Introduction sections increased from 11.5% (3/26) to 61.8% (21/34). The proportion that mentioned a systematic review in their Discussion sections increased from 23.1% (6/26) to 52.9% (18/34).

Discussion

Discussion

In 2022, two systematic reviews were published of studies that, similar to ours, had investigated the use of systematic reviews in the design of new research or in reports of the findings of research. The findings of those reviews are not inconsistent with our overall findings. Nørgaard and colleagues sought to identify and synthesize the results of meta-research studies of the use of systematic reviews to design new health research studies. They included 16 studies published from 2005 to 2021. In these reports, the proportion using a systematic review to inform the design of a new study ranged from 0% to 73% (mean: 17%) (Nørgaard et al, 2022). Draborg and colleagues (2022) identified and synthesised results from meta-research studies that had assessed whether reports of health research studies had used systematic reviews to present their findings in the context of data from similar studies. They included 15 meta-research studies published between 1998 and 2021 (including our previous five audits). They calculated that a mean percentage of 30.7% (range: 9% to 48%) of the original studies had placed their findings in the context of existing studies (Draborg et al, 2022).

More recently, Jia and colleagues (2023) reported a cross-sectional survey that used 737 Cochrane Reviews published up to October 2021 to identify 4003 RCTs that had been published at least two years after the first version of the review and were included in an updated version. These RCTs were published between 2007 and 2021 and Jia and colleagues screened their references to identify citations of prior Cochrane or other systematic reviews. They found that 56.6% (2265/4003) of the studies cited one or both types of systematic review, and 43.4% (1738/4003) did not cite any systematic reviews. The percentage of RCTs not citing any systematic review decreased from 64.5% (118/183) in reports published in 2007 or 2008, to 28.4% (29/102) of reports published in 2020 or 2021 (Jia et al, 2023).

In keeping with those other studies, we have found that over the 25 years of our audits many reports of RCTs failed to make best use of systematic reviews. They have thus failed to provide readers of their research with robust evidence to support decision making in practice or in planning new research. However, over the past decade there has been an increase in the use of systematic reviews in the Introduction and Discussion sections of reports of RCTs. In the five major general medicine journals we assessed, the proportions citing systematic reviews increased from 27.7% and 27.0%, respectively, in 1997-2012, to 61.8% and 52.9% in the 2022 sample. It is uncertain whether this represents progress with the concept of evidence-based research (Lund et al, 2021a; Lund et al, 2021b) or simply that systematic reviews have become more common and therefore easier to identify and cite (Clarke & Chalmers 2018), with a particular boost during the COVID-19 pandemic (Dotto et al, 2021). However, there remains substantial room for improvement, with 37.9% (10/27) of the reports from May 2022 that did not claim to be the first RCT making no systematic attempt to place the RCT’s design in context in their Introduction sections, and 33.3% (9/27) failing to do so for the findings of the RCT in their Discussion sections.

Improvements in this area are now much easier than when our ‘Islands audits’ began in 1997, with tens of thousands of systematic reviews being published every year. (Clarke & Chalmers 2018). Furthermore, Glasziou and colleagues recently illustrated three ways to incorporate new findings in systematic reviews in the Discussion sections of a new study, viz:

- conduct an updated systematic review after running an updated search and present an up-to-date meta-analysis;

- add the new RCT result to an existing systematic review which requires extracting the summary results for each RCT from a previous meta-analysis, adding those for the new RCT and combining the results, without a new search; or

- add the results of the new RCT to the previous summary results to generate an updated summary result, without a new search (Glasziou et al, 2024).

Where the existing review is a Cochrane review, the second and third methods are particularly easy because data files can be downloaded from the Cochrane Library for all Cochrane Reviews. This facility provides the basis for calculating a revised estimate of the average effects of the intervention and also makes it easier to compare the findings of the new RCT with those of the studies that preceded it.

This type of cumulative meta-analysis would also highlight the value, or not, of the new RCT to the existing evidence base (Clarke et al, 2014). This is important. If practitioners, policy makers and the public do not have access to the most up-to-date evidence on the effects of interventions, there will be delays in implementing effective treatments and in abandoning interventions that are ineffective or harmful. Failure to address these deficiencies will affect health and sometimes lead to preventable deaths and chronic morbidity.

In an article entitled ‘Modifying the process of science’, Hahn and Teutsch used the findings of the 1992 study reported by Antman and colleagues (Antman et al, 1992)) of what cumulative meta-analyses would have shown about the effects of interventions for patients with acute myocardial infarction. They estimated that failure to conduct routine prospective cumulative systematic reviews had resulted in more than 150,000 deaths annually in the United States alone, from non-use of intravenous vasodilators, aspirin and ß-blockers and from continued use of anti-arrhythmic drugs (Hahn & Teutsch 2021). They called for “modification of the process of science” (Hahn & Teutsch 2021), like others before them. For example, Collins, Doll and Peto estimated that tens of thousands of preventable deaths had occurred due to the informed consent procedure required for extension of recruitment to the ISIS-2 trial in the United States (Collins et al, 1992).

Conclusions

People making decisions about health care need to feel confident when using reports of RCTs. This requires RCTs to be designed in the light of systematic assessments of other similar research, so ensuring that they are really needed, and that they will address relevant, unanswered questions. It also requires RCTs to be reported in the context of other similar research, to ensure that users are able to consider the totality of the relevant evidence. This will need increased recognition that the conduct of RCTs and systematic reviews should not be seen as independent endeavours to be done by separate researchers, but that they should go hand-in-hand. (Mahtani 2016).

Those who fund and do RCTs and those who oversee their publication and use have an ethical responsibility to ensure that this research is reported in proper context. If this happens, anyone who repeats our ‘Islands audit’ in years to come will be able to conclude with confidence that, in the medical literature: ‘no trial is an island, entire of itself,’ and that the findings of every RCT can be seen ‘in the context of the main’. This means the totality of the evidence for improving health and preventing premature deaths. However, unless the deficiency we have shown over the past 25 years is addressed by the research community, people are likely to continue to suffer and die unnecessarily because of a lack of a reliable evidence base for health care.

Additional information

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the design and conduct of this study. MC drafted the first version of this manuscript and analysed the data. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

All authors have been strong advocates of the importance of the use of systematic reviews to inform the design and interpretation of randomised trials.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not required for this audit of published articles.

Primary funding source

This study received no dedicated funding.

Data sharing

The data used in this report are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Paul Glasziou for his review of an earlier version of the manuscript including that we show the data as stacked bar Figures, and to Patricia Atkinson and Jan Chalmers for their help with earlier drafts.

References

Antman EM, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC (1992). A comparison of results of meta-analyses of infarction. JAMA 268(2):240-8.

Chalmers I, Altman DG (1999). How can medical journals help prevent poor medical research? Some opportunities presented by electronic publishing. Lancet 353:490-3.

Clarke M (2004). Doing new research? Don’t forget the old. Nobody should do a trial without reviewing what is known. PLoS Medicine 1(2):100-2.

Clarke M, Alderson P, Chalmers I (2002). Discussion sections in reports of controlled trials published in general medical journals. JAMA 287:2799-801.

Clarke M, Brice A, Chalmers I (2014). Accumulating research: a systematic account of how cumulative meta-analyses would have provided knowledge, improved health, reduced harm and saved resources. PLoS ONE 9(7):e102670.

Clarke M, Chalmers I (1998). Discussion sections in reports of controlled trials published in general medical journals: islands in search of continents? JAMA 280:280-2.

Clarke M, Chalmers I (2018). Reflections on the history of systematic reviews. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 23(4):121-2.

Clarke M, Hopewell S (2013). Many reports of randomised trials still don’t begin or end with a systematic review of the relevant evidence. Journal of the Bahrain Medical Society 24(3):145-8.

Clarke M, Hopewell S, Chalmers I (2007). Reports of clinical trials should begin and end with up-to-date systematic reviews of other relevant evidence: a status report. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 100:187-90.

Clarke M, Hopewell S, Chalmers I (2010). Clinical trials should begin and end with systematic reviews of relevant evidence: 12 years and waiting. Lancet 376:20-1.

Collins R, Doll R, Peto R (1992). Ethics of clinical trials. In: Williams CJ, ed. Introducing new treatments of cancer: practical, ethical and legal problems. Chichester: Wiley, 49-65.

Donne J. Devotion upon emergent occasions. Meditation 17.

Dotto L, Kinalski MA, Machado PS, Pereira GKR, Sarkis-Onofre R, Dos Santos MBF (2021). The mass production of systematic reviews about COVID-19: An analysis of PROSPERO records. Journal of Evidence Based Medicine 14(1):56-64.

Draborg E, Andreasen J, Nørgaard B, Juhl CB, Yost J, Brunnhuber K, Robinson KA, Lund H (2022). Systematic reviews are rarely used to contextualise new results-a systematic review and meta-analysis of meta-research studies. Systematic Reviews 11:189.

Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, Michie S, Moher D, Wager E (2014). Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet 383:267-76.

Glasziou P, Jones M, Clarke M (2024). Setting New Research in the context of Previous Research: some options. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 29(1):44-6.

Hahn RA, Teutsch SM (2021). Saving Lives by Modifying the Process of Science: Estimated Historical Mortality Associated with the Failure to Conduct Routine Prospective Cumulative Systematic Reviews. American Journal of Biomedical Science and Research 14(6):AJBSR.MS.ID.002052

Jia Y, Li B, Yang Z, Li F, Zhao Z, Wei C, Yang X, Jin Q, Liu D, Wei X, Yost J, Lund H, Tang J, Robinson KA (2023). Trends of Randomized Clinical Trials Citing Prior Systematic Reviews, 2007-2021. JAMA Network Open 6(3):e234219.

Lund H, Juhl CB, Nørgaard B, Draborg E, Henriksen M, Andreasen J, Christensen R, Nasser M, Ciliska D, Clarke M, Tugwell P, Martin J, Blaine C, Brunnhuber K, Robinson KA; Evidence-Based Research Network (2021a). Evidence-Based Research Series-Paper 2: Using an Evidence-Based Research approach before a new study is conducted to ensure value. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 129:158-66.

Lund H, Juhl CB, Nørgaard B, Draborg E, Henriksen M, Andreasen J, Christensen R, Nasser M, Ciliska D, Tugwell P, Clarke M, Blaine C, Martin J, Ban JW, Brunnhuber K, Robinson KA; Evidence-Based Research Network (2021b). Evidence-Based Research Series-Paper 3: Using an Evidence-Based Research approach to place your results into context after the study is performed to ensure usefulness of the conclusion. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 129:167-71.

Mahtani KR (2016). All health researchers should begin their training by preparing at least one systematic review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 109(7):264-8.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, Elbourne D, Egger M, Altman DG (2010). CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340:c869.

Nørgaard B, Draborg E, Andreasen J, Juhl CB, Yost J, Brunnhuber K, Robinson KA, Lund H (2022). Systematic reviews are rarely used to inform study design – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 145:1-13.